I’ve observed a lot of conversations on Facebook in various WWII groups the last couple of months, in which people ask how to proceed with WWII research. The information in these groups is often helpful but often, the members do not have a firm grasp on how to proceed without wasting a lot of time and money.

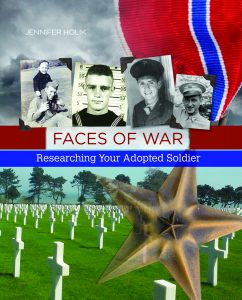

by Jennifer Holik

Many people have a general idea of which battles their relative participated in and often a Division or Unit. Rarely do they have a timeline of service created or know specifically when the soldier was in each unit and where he was. Too often, people assume their soldier was with a particular unit the entire war. Unfortunately this is usually not the case. Soldiers were often transferred within a Division to different companies. In many cases, they were transferred from their Division into a replacement depot and into an entirely new Division. Soldiers who were wounded and did not return to their original unit within 30 days were often sent to a replacement depot to await a new assignment.

Heading straight into unit records based on limited knowledge may cause you a lot of wasted time and potentially money if you request records or hire a researcher, without first knowing for sure where your soldier was and in which unit. I’ve heard of many people just pulling unit records and later discovering their soldier was not with that unit except for a few days or weeks.

When I comment in these groups I try to stress there is a process by which we do this research. I also stress the importance of hiring a researcher to help you obtain some or all of the records. WWII research is not free no matter how you do it. When you follow the process, you will often end up saving yourself a lot of time and money. To help you understand a bit about the process, I have several tips for you.

1. Create a Timeline of Service

The first thing you should do is create a timeline of service based on what you know about your soldier’s service history. A timeline should list the date (either full or a year) and the event which happened. Noting where you found that information, even if it was a family story, is important. A timeline of service may look like the following:

January 1942 – Adam Jones joins the 1st Infantry Division

November 1942 – North Africa Campaign

July 1943 – Sicily Campaign

30 July 1943 – Wounded in the Sicily Campaign

February 1944 – Hospitalized in England

June 1944 – Normandy – D-Day Campaign

2. Do your homework

After you create a general timeline, search your home and ask your family to look for documents and photographs that provide clues.EVERY clue you find may help, even if it conflicts with another piece of information you have. Write it all down and cite the source.

Look at the Checklists and Forms I provide on this site for help with your homework. There are many resources each of us has within our home that we might not consider have information.

3. Obtain the OMPF and Company Reports

Next, order the Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, MO. You need several pieces of information, if possible, when submitting a request.

Soldier’s full name

Date and place of birth

Service Number (this is not the individual’s Social Security Number)

Branch of service

Dates of service (enlistment, discharge or death)

Theater(s) of war

Unit(s) in which he or she served

The least expensive way to begin a search is to fill out Form 180 on the NPRC website (http://www.archives.gov/research/order/standard-form-180.pdf) and see if the file survived. If records are discovered, NPRC will send you a letter indicating such, as well as your fee for copies. Form 180 will ONLY search personnel records.

National Personnel Records Center

1 Archives Drive

St. Louis, Missouri 63138

You can visit the NPRC in-person, but there is a procedure for doing so. Visit their website for current rules regarding making an appointment, what is allowed in the research room, and how to request files and microfilm.

Another option is to hire a researcher, such as myself, who is able to obtain and analyze the records available. There are many more valuable records at the NPRC besides the service files, such as Morning Reports, that Form 180 will not search for you.

4. Analyze the Information & Start Writing the Story

One of the most important parts of the research process is writing the story. Writing does not necessarily mean you need to publish a book. Writing the story allows you to see where there are errors or gaps in your research. It allows you to formulate new research questions and therefore search for new materials.

When you obtain new information, add it to your timeline of service. Analyze the information and go through all your previously obtained records with a fine tooth comb. Make sure you understand what information is presented, especially if any of it conflicts. People made mistakes in records then just as we do today. No one is perfect.

5. Look for Unit Records

Finally, once you have a firm understanding of which units your soldier was in and when, you can begin looking for unit records. These records will provide a greater context of battles and additional training your soldier received. You may not locate your soldier’s name in many of these records but you will understand the battles and overall context of the war.

Learn more about research and Jennifer’s work: JENNIFER HOLIK

Recommended