Like Jochen Peiper’s ambition mission to reach the Meuse River, the desperate German parachute operation that had been intended to help hold the roads open so that the passages across that river could be seized, came to an ill end. Unternehmen Stösser had been intended to spring Kampfgruppe Kuhlmann and SS Panzer Regiment 12 to come to Peiper’s aide along his exposed northern right flank. Indeed the secret parachute operation aimed to block the American reinforcements, now streaming down from the north. Kuhlmann had become mired in muddy trails leading up to the twin villages of Rocherath-Krinkelt and then again at Dom Bütgenbach coming face to face with the muscular resistance of the U.S. 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions. In repeated attempts, they failed to unhinge the right flank of the German assault.

by Danny S Parker, author of FATAL CROSSROADS and HITLERS WARRIOR www.dannysparker.com

In many ways, the parachute operation of Kampfgruppe von der Heydte was like a canopied mirror of the failure of Peiper’s SS panzer arm in the Ardennes. The thousand man parachute operation had absorbed most of the Fallschirmjäger still with drop experience in the German army: spanning the gamut from those with just six jumps at Wittstock the previous August, to the hard-bitten survivors of Crete. They had come from all sectors of the German Luftwaffe in the last few weeks of autumn to jump into a desperate operation to serve and even more desperate offensive.

At 2 AM, Sgt. Willi Volberg, in the Stösser assault group remembered loading into the old Ju-52 transports at Lippsringe air field and nervously singing the Fallschirmjäger’s hymn. Belting out the words, they adjusted parachutes and drop gear in the cramped and dimly lit cabin:

“Rot scheint die Sonne, fertig gemacht, wer weiss ob sie morgen für uns auch noch lacht…” (Red shines the sun already! Who knows if the morning will laugh with us again!)

It was totally dark as they sang, and any red sun of morning seemed a long time away. How could there be any in this fog?

“Werft an die Motoren, schiebt Vollgas hinein . Startet los, flieget ab, heute geht es zum Feind!” (The engine starts up, full throttle given. Start, leave, take off. To the enemy we go!)

Now, the BMW radial engines now roared to life and drowned out the nervous whispers among the Green Devils:

“Flying westwards now, the pilots were assisted by the beams of searchlights towering into the nightly sky to direct the pilots to the drop zone. The crew members were generally inexperienced and, to a great extent, performed the task for the first time. To avoid collision, they used navigation lights and by this, when flying over the front area, made easy targets for the U.S. anti-aircraft artillery….Finally, we were alerted by the command to ‘great read for the jump out’ soon followed by the signal horn. I repel myself vigorously with my hands and feet, before I am pulled downwards by the weight of my body, arms and equipment. When the parachute opens at a stretch, I nearly go head over heels. Afterwards, swinging in the straps, I notice the noise of the engines becoming more and more gentle…After bouncing against the ground, I tumble down a small slope, then being pulled upwards again by the parachute….my sliding ends because the parachute becomes tangled in a fir. I quickly loosen the straps and free the automatic rifle ready for combat…Nothing is to be seen of the parachute flare bombs illuminating the drop zone…”

Right: Baron von der Heydte at the Ardennes Photo courtesy of Danny Parker

To be sure, the paratroop battlegroup was weak; the old Auntie Ju transports having been severely scattered by high winds from American anti-aircraft fire played havoc with inexperienced pilots. Most of one company fell will-nilly in the pine woods around Eschweiler and Kornelimünster east of Aachen. Having jumped at 3 AM on 17 December, the youth and elder Fallschirmjäger alike, now still remained in the woods, waiting to be relieved by Kuhlmann or Peiper’s tanks. Some, like Willy Volberg, were simply lost and looking to find anyone friendly:

“Nothing is to be seen of the signal flares marking the assembly area. So, after several hours of daylight, only two sergeants, 13 privates and myself as an officer candidate attached to the parachute platoon– have met each other. Despite searching eagerly, we find neither the rest of our comrades nor a single one of the supply containers…One of our fellows think we are in Switzerland! We too, at first, cannot identify our location because of blowing snow, but it clears at one moment and we can see the Gileppe dam in the distance. So, on the map, we are able to locate our position now. We have dropped about six km northwest of the planned point….There is only one casualty in our small group; one of the fellows complains fo a sprained knee, but he bravely hold his position in our march eastward…”

Like Peiper, their parachute operation which Hitler conceived with the rampaging SS tank corps to send the Allies reeling was now itself in danger of encirclement. Still, about half of the paratroops actually landed near the wind-swept frozen marsh of the Haute Fagnes although widely dispersed. By the end of the first day, von der Heydte only had collected 125 men in the area of the designated drop zone– not nearly enough to fulfill its mission. Volberg continues:

“Just before noon, we contact a German reconnaissance patrol– at first thinking it an enemy element– scouting towards Verviers. Advised by this patrol, we soon meet our unit at the crossing. But what is up here? Meanwhile, about 130 paratroopers (including ourselves) have met here, and even after the arrival of another 150 men, we form only a small part of the original task force…We occupy positions nearby the crossing. Reconnaissance patrols are sent different directions. A party under my command is to reconnoiter towards Baraque Michel and south of this hamlet. Enemy contact is to be avoided. All patrols return with information on the enemy highly important to higher echelons, but how to transmit this information without a radio.”

First Hiding Place

Later, by scouring the nearby woods, von der Heydte’s group slowly rounded up those lost and straggling. Still many were missing. In the wide areas of the snow-covered pine woods above Malmédy a number of German parachutists with broken legs died a slow death of starvation, freezing and exhaustion. Their numbers were still being discovered by locals the following spring. The night after the operation, another reinforcement operation with a few planes was flown from Paderborn to provide supply and a few more troops for the 4th Kompanie. Yet, that effort came to naught as anti-aircraft fire was even worse and only a few containers reached the lost Stösser group.

With no further food or resupply von der Heydte’s situation soon turned grim. His paratroopers were to have been relieved by December 18th at the latest. Indeed, Dietrich had promised von der Heydte a couple of weeks earlier that he would personally meet him at the crossroads. But now it was two days later and the battle group was completely out of communication with the outside world. A four-man portable communications squad of SS men from Hitler Jugend Panzer Division of 7. Batterie under SS Ostuf. Harald Etterich had jumped with a 35 watt Type 10 radio. The paratroopers joked that these SS “tough guys” had been scared to death when they had to jump out of an airplane.” But worse was that only one of the radio set from the 12.SS Panzer Division wasn’t working– having been “smashed to pieces bouncing on the ground.” Then too, most of the organic signals platoon floated down in front of surprised Volksgrenadiers just south of Monschau. If Hitler Jugend’s artillery regiment could reach Elsenborn, they would be able to call down fire to support von der Heydte’s men with their 15 cm field howitzers or a long-range battery of K-3 guns. Without communications, that hope was dashed.

The Baron had originally wanted carrier pigeons for his battlegroup, but had been overruled in the unpleasant alcoholic encounter with Sepp Dietrich. The assembled paratroopers were well equipped with ammunition, but lacking in the weapons themselves– only 15 machine guns, two 8 cm mortars, numerous Panzerfaust along with an assortment of 98 K rifles, Sturmgewehr 44 assault rifles and machine pistols. With all radios lost and only a single working mortar, von der Heydte deemed it possible to mount onlly a single combat action to seize the Baraque Michel crossroads when the 12. SS Panzer Division approached.

Von der Heydte and his group built a defense perimeter in the woods 2-3 km NE of the crossroads:

“The first day brought no strong contact with the enemy. The group that had reached us from the north brought with them about 30 prisoners and a few more had been taken by reconnaissance patrols. A few enemy armored and unarmored vehicles were destroyed. American reconnaissance patrols did not try to establish contact until afternoon. I decided, therefore, to shift position during the night. We moved about 3 km to the north, onto a hill offering good observations south and southwest. Before moving up, I released the prisoners and sent them with some of our own wounded…The following day was spent without contact with the enemy…The sound of battle was far off and the camps at Elsenborn and Malmédy were apparently still strongly held by the enemy.”

On the night of 17-18 December, an attempt was made to supply the paratroopers with extra food, ammunition and a 36 man heavy platoon. Three Ju-52s left Sennelager/Paderborn for the Ardennes at 1900 on 17 December, but this operation too came to little. Waiting for days, the only tanks that approached were American ones searching for the enemy paratroopers. On December 19th the Americans attempted to flush out von der Heydte’s combat team northeast of the Mont Rigi. A brief firefight erupted as the combat team pulled back to the east, but with three paratroopers being wounded. Now, Von der Heydte pulled back deeper into the woods east of Mont Rigi where the Americans on their tanks and trucks could not easily reach them.

Still, the men were hungry, no food in two days and cold– there were only a few blankets, and no fires could be lit. Still spirits were still high and Allied interrogators capturing several members found them possessing a near “mystic belief” in their leader, von der Heydte that somehow prospects could be salvaged. On the afternoon of 19 December, an eight man search party was sent out to search for the missing parachute food containers. They found two containers, but only with ammunition for which there were no weapons and a Panzerfaust. During the search two of the men were captured and the rest returned on Tuesday night without any food.

It was clear that his men would soon succumb to cold and hunger. At dark, von der Heydte pushed east with his men, releasing his American prisoners, asking them to take on his own wounded. By midnight his eastern trek had reached the Helle and forded its icy waters near the place where a little stream– Ruisseau de petit Bonheur– flowed into it. The men were forced to wade and drench themselves in the cold water. They intended to move to up beyond its steep bank to the east towards Neu Hattlich, but again ran afoul of American infantry searching for them. After an exchange of shots another paratrooper was wounded and von der Heydte pulled back to the west bank of the stream and organized an all-around defense near Hill 584. The Americans, meanwhile, thought they “had 200 paratroopers cornered” just before dark on 20 December east of Monshau, only to have their quarry slip away.

The following morning, von der Heydte spied a U.S. skirmish line on the other side of the creek, searching for them. Still, it was with total surprise when at noon 20 December Obst. Von der Heydte gave out an order that stunned the remaining hungry and tired paratroopers in his guerilla warfare band. His men to separate into small groups, he urged them, and try to make their way back to German lines. Those that made it back to Germany were to assemble at the Truppenübungsplatz– the exercise field– at Köln-Wahn where they were to receive long-promised Christmas furloughs.

Not long after the final instruction were given, the encampment in the woods was broken up when the Americans pushing into the Königliches Torf Moor scrub-brush and woods, began firing again. To the east, he could hear the metallic squeal of tanks approaching from CCB 3rd Armored Division along the road from Eupen to Monshau. Some of the paratroopers threw away their heavy weapons and scattered into the woods. Yet, for the most part the Fallschirmjäger slipped away intact. Still, Willy Volberg was depressed.

“I am shocked, for I never thought our airborne operation would end like this. At first, according to the commander’s order our squad breaks down into several segments march in intervals along the Sour creek towards Eupen…we make our way southwest, cross the road leading from Eupen to Malmédy without being notice and then turn to the northwest for a stretch of about a kilometer. There should now be sufficient distance between us and the enemy. We hide in the underbrush and make use of fir branches a resting place…We are all going to sleep. If our hiding place is discovered by the Americans, there is nothing to do but surrender…Before falling asleep, I remember a trolley line from Eupen via Aachen to Eschweiler which is my native place. In peace time I would be able to reach this place within two hours. However, U.S. forces have been occupying Eschweiler since November 1944. I finally fall asleep with the taste of potato pancakes and applesauce in my mouth— just an illusion of hunger.”

Amazingly, after waking from his dream the following morning, Volberg and his companions stumbled on two parachute containers when one of their little group went to relieve himself. One of the relief containers to be sent to them! Suddenly, they are loaded with all the ammunition they can take, but more importantly by “chocolate, bread, rusk and cheese in tubes.”After everyone in his little squad feasted on the victuals, Volberg and company hiked cross country through the dense forests, suffering cold, exposure and painfully chaffed thighs. In the late afternoon of the 22nd, they finally reach the Eupen-Mützenich road, Volberg benefitting from native knowledge of the surrounding terrain. The next day, the exhausted group managed to reach Reinartzhof, north of Monschau having several times to avoided noisy American outposts of the U.S. 78th Infantry Division; more slogging through mud and marsh.

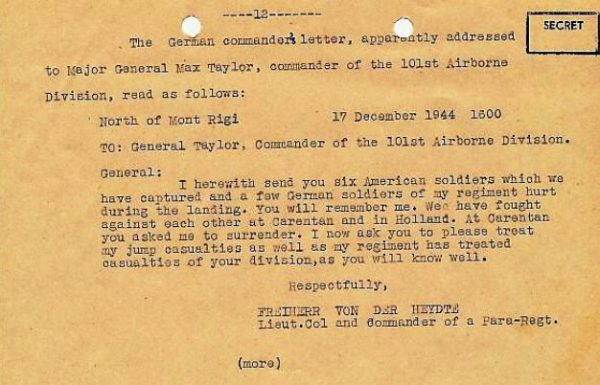

On 17 Dec 44 and without any intelligence about the American troops near Monschau,the Baron wrote this note to Gen Max Taylor of the 101st ABN, who, at that time was back in the US. The 101st Division was still in Mourmelon, France, and would not be committed to the battle until 19 December.

Fretting over interconnecting American foxhole line just ahead of them, Volberg and his miserable companions found themselves suddenly engulfed in a heavy snow. Yet, even shivering in their Knochensack– the waterproofed parachutist’s camouflage blouse– the thick snow seemed a Christmas godsend. Seizing the momentary white-out as cover, Volberg ordered everyone to rush forward firing their guns at full volume. That done, the American outpost dove fore cover. Within seconds the German paratroopers are through the U.S. line running for their lives as the Americans recovered from their surprise and sent bullets over their heads in the snowstorm. All of the desperate paratroopers kept running and none were hit. Presently, Volberg confronted equally befuddled Landsers of the 272.Volksgrenadier Division. About 150 of the men with von der Heydte escaped back to German lines, many near Kalterherberg. Others were captured, but often after being turned over to the U.S. Army military government in Monshau by locals.

Continue reading at : Operation Stösser: Kampfgruppe Von der Heydte in the Ardennes (part II)

Danny S Parker, author of FATAL CROSSROADS and HITLERS WARRIOR