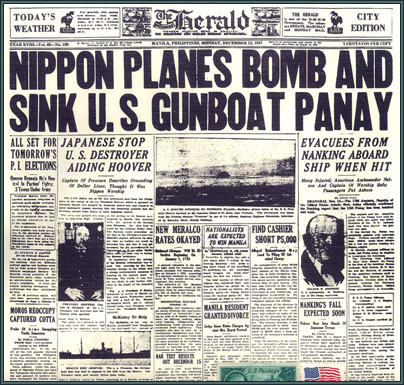

On 12 December 1937 the United States gunboat USS Panay (PR-5) was sunk by aircraft of the Japanese Imperial Navy while anchored on the Yangtze River in China. Although probably unintentional, this attack exacerbated the already tense relationship between the Japanese and American governments. The sinking of the Panay constituted the most serious affront to the presence of American military forces in China, presented a very real challenge to the peaceful relations between the United States and the Empire of Japan, and provided the United States with proof positive as to the Japanese military’s control over the development of Japanese foreign policy.

by Martin K A Morgan

THE PANAY INCIDENT AND THE INEVITABLE TUMBLE TOWARD WORLD WAR II IN THE PACIFIC

IN MEMORY OF THE ILL-FATED CRAFT PANAY AND HER CREW

‘Beguiled by the rough mischievous waves and amid the din and turmoil of the battle, the heroes of the air, eager to chase the fleeing foe bombed, alas! by mistake, a ship not of the enemy but of the friendly neighbor country, which sank with a few sailors aboard.The source of the nation-wide grief, which knows no bounds, that fatal missile was.’ (note presented to Ambassador Joseph Grew by a Japanese civilian).

The USS Panay, a shallow draft gunboat designed specifically for riverine operations, displaced a mere 450 tons. Its armament consisted of only ten .30-cal. Lewis guns and a pair of 3 inch naval guns. River patrol craft by the very nature of their intended purpose are built under the restrictions imposed by the close quarters of their operating environment, and as a result are not very heavily armed. Eight vessels similar to the Panay made up the U.S. Navy’s Yangtze Patrol. Command and control fell on the shoulders of Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, Commander-in- Chief of the United States Asiatic Fleet who directed the Yangtze Patrol from his flagship USS Luzon (PG-47). The need to post a contingent of U.S. Navy patrol craft on the Yangtze grew out of the need to protect American citizens and business interests in China. China had not long before been the home of organized bandit armies that struck with impunity in a constant search for plunder. For a short period of time Americans fell victim to these bandits and American businesses lost a great deal of money as a result, but the United States government quickly responded by creating the Yangtze Patrol. The program successfully eliminated the once threatening bandits. However, its role dramatically changed in 1937.

The port city of Shanghai capitulated on 12 November 1937 after a total of 92 days of siege on the land, in the air, and on the sea. With that, the Japanese had gained control of the headwaters of the Yangtze. The Japanese offensive in China was then aimed 200 miles upriver at the city of Nanking. When it became clear that the Chinese intended to defend the city, and that the Japanese intended to attack as they did in Shanghai, preparations for battle commenced. On 22 November came the evacuation order which affected most of the U.S. Embassy staff in Nanking. Embassy personnel boarded the USS Luzon which withdrew to the relative safety of Shanghai and a small contingent of staff remained to communicate the unfolding events in the city to the outside world and to protect a few stubborn westerners determined to stay in Nanking. Businessmen and reporters made up the group of civilians who remained. To provide for the evacuation of these westerners, the USS Panay stayed behind.

Japanese bombers raided the city in preparation for a ground assault, and thereby created a critical situation. In addition to the Panay, several other neutral vessels remained moored to the docks at Nanking. This information was communicated to the Japanese government through the American Ambassador in Japan. The situation deteriorated to the point that, on 7 December all westerners boarded neutral vessels at night for their own protection. During the day, the civilians could come and go as they pleased to take care of business. This lasted until 9 December when Japanese machine gun nests began to spray the walls of the city with bullets. On that day the westerners returned to the Panay for the evening by 1500 only to learn that the Japanese had urged all foreign nationals to evacuate the city. Panay and several other neutral vessels then proceeded up river two miles in an effort to avoid the nightly shelling and bombings. The ships dropped anchor and waited in the middle of the Yangtze until, on 11 December a Japanese artillery unit shelled them. The group immediately weighed anchor and advanced further upriver in attempt to move out of range of the guns. None of the vessels suffered any damage, but some of the shells fell as close as fifty feet away from the British gunboat HMS Scarab. The artillery barrage had the effect of driving the foreign boats further away from the city. The Panay spent the night four miles above Nanking and the following morning (12 December) moved further upriver in the company of three steamers owned by the Standard Oil Company of America (the SS Meiping, the SS Meihsia and the SSMeian). At 0900, a motor boat carrying 20 Japanese soldiers approached Panay. Two officers and four heavily armed soldiers with bayonets fixed boarded the gunboat and inquired as to Panay’s reason for proceeding upriver. After a few tense moments, the Japanese seemed to accept the explanation that the fighting downriver motivated the relocation of the Panay and the Standard Oil steamers, and they departed. Panay and the steamers then continued to a point 27 miles above Nanking and all three dropped anchor.

At 1330 all four vessels (Panay and the three Standard Oil steamers) came under attack by a flight of 24 high level bombers, dive bombers, and fighters of the Japanese Imperial Navy. For 20 minutes the Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed the four ships. Some of the crew of the Panay returned fire using the.30-cal. Lewis machine guns, but to no avail for none of the attacking aircraft suffered even a single hit. The high level (horizontal) bombers released their bombs from an altitude of approximately 5,000 feet, the dive bombers released their bombs from an altitude of approximately 1,000 feet while in a 60 degree near-vertical dive, and the fighters employed their machine guns while fifty feet above the surface of the water, a height at which conspicuous markings presumably could be seen. Five bombs hit Panay and she began to list to starboard. In an effort to remove some of the wounded sailors from the fray, a small motor launch made a run for the shore. During its trip it was machine gunned by one of the Japanese fighters, wounding one sailor. After the attacking aircraft departed the area, the Captain ordered the ship abandoned, and all hands transferred to the shore.

At 1330 all four vessels (Panay and the three Standard Oil steamers) came under attack by a flight of 24 high level bombers, dive bombers, and fighters of the Japanese Imperial Navy. For 20 minutes the Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed the four ships. Some of the crew of the Panay returned fire using the.30-cal. Lewis machine guns, but to no avail for none of the attacking aircraft suffered even a single hit. The high level (horizontal) bombers released their bombs from an altitude of approximately 5,000 feet, the dive bombers released their bombs from an altitude of approximately 1,000 feet while in a 60 degree near-vertical dive, and the fighters employed their machine guns while fifty feet above the surface of the water, a height at which conspicuous markings presumably could be seen. Five bombs hit Panay and she began to list to starboard. In an effort to remove some of the wounded sailors from the fray, a small motor launch made a run for the shore. During its trip it was machine gunned by one of the Japanese fighters, wounding one sailor. After the attacking aircraft departed the area, the Captain ordered the ship abandoned, and all hands transferred to the shore.

Just as the crew reached safety, a Japanese motor boat appeared and approached the sinking gunboat. When the Japanese boat was within a distance of about 200 yards, the troops on board sprayed the wreckage of the Panay with machine gun fire. Then five Japanese soldiers boarded the sinking 9unboat. According to the survivors, these Japanese soldiers lingered for five minutes, then returned to their motor boat and left the area. The USS Panay sank with colors flying at 1554 12 December 1937.

After the Panay sank, the survivors began an a two day long trek across very inhospitable terrain. The crew barely had time to abandon ship with the wounded so they did not collect supplies. Operating under the impression that the attack was intentional, the survivors feared that they would be hunted down and killed. For that reason, no attempt was made to flee the scene until after nightfall. The beleaguered crew reached the hamlet of Hohsien where, after some yelling and shouting, they convinced the Chinese within the walls to open the gates and allow them to enter. In China a solid wall enclosed every settlement no matter how big or how small – an indication of the severity of the former bandit problem. The civilians in Hohsien provided medical assistance and hot food. This crew especially welcomed this considering that they had been outdoors for over 12 hours in the cold of December. Still fearing the Japanese, the survivors mounted-up and left Hohsien the following morning heading for the city of Hansham 20 miles away. They hired some peasants to transport them to Hansham in river junks and although it took more time than walking, the boat trip provided more comfort for the wounded, some of whom could not walk. The convoy of junks arrived outside of Hansham at 0400 and the crew waited until first light to approach the walls of Hansham. The fact that every Chinese town in the area of Nanking feared attack convinced the crew to do this. So they waited in the cold. When dawn finally arrived and the crew approached the city walls, the town magistrate greeted the Americans with instructions for them to return to Hohsien where they would find three gunboats (one U.S. Navy and two Royal Navy) ready to take everyone to Shanghai. Again the junks transported the crew. Upon their return to Hohsien, they found the gunboats which the magistrate in Hansham mentioned as well as several Japanese river craft. The USS Oahu (PR-6) – coincidentally the sister ship of the Panay12 – the HMS Ladybird, and the HMSBee embarked the survivors, the wounded, and bodies of the three men who died and ended the 48 hour ordeal.

The series of events which followed the rescue of the survivors of the Panayincident proved to be equally as important as the sinking. Unlike the relatively short frame of time taken up by the attack and subsequent rescuer political machinations continued for several months. The American Ambassador in Japan, Joseph C. Grew knew all too well the danger inherent in the presence of American military and civilians in close proximity to a foreign conflict. WhenPanay left the docks on 9 December for the last timer Grew informed the Japanese government of the move. When news that Japanese artillery shelled the Panay on the 10th in an effort to drive her further upriver reached Grew, he called on the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs Koki Hirota and appealed to him (Hirota) to take any necessary steps to restrain the Japanese military in China from indiscriminately attacking any Americans again. Grew, apparently anticipating trouble, also warned Hirota that any incident resulting in the injury of American nationals would have serious repercussions in the United States.

The series of events which followed the rescue of the survivors of the Panayincident proved to be equally as important as the sinking. Unlike the relatively short frame of time taken up by the attack and subsequent rescuer political machinations continued for several months. The American Ambassador in Japan, Joseph C. Grew knew all too well the danger inherent in the presence of American military and civilians in close proximity to a foreign conflict. WhenPanay left the docks on 9 December for the last timer Grew informed the Japanese government of the move. When news that Japanese artillery shelled the Panay on the 10th in an effort to drive her further upriver reached Grew, he called on the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs Koki Hirota and appealed to him (Hirota) to take any necessary steps to restrain the Japanese military in China from indiscriminately attacking any Americans again. Grew, apparently anticipating trouble, also warned Hirota that any incident resulting in the injury of American nationals would have serious repercussions in the United States.

The Second Secretary of the American Embassy in China, George Atcheson communicated the 12 December movement of the Panay to the Japanese from his temporary office onboard the gunboat. Due to the transient nature of the Panay no anchorage location could be entered on any Japanese maps, so they removed the Panay from their maps with the intent to re-enter it once it reached its destination. The Panay anchored 27 miles above Nanking at 1100 on the 12th and the attack began at 1330. Although Atcheson communicated the location through all the proper channels a sufficient window of time existed during which the Japanese had no indication marking the location of thePanay and the three Standard Oil steamers.

Confirmation of Grew’s apparent premonition came on the 13th when Hirota telephoned the American Embassy to request a meeting. Based on this phone call, Grew correctly surmised that trouble had finally manifested itself. The unprecedented step of the Minister for Foreign Affairs himself (a high ranking government official) to request a meeting with a mere foreign ambassador indicated a degree of urgency. Grew usually dealt with the Director of the American Bureau of the, Japanese Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Seijiro Yoshizowa. From this, the very first official Japanese reaction to the sinking, the Japanese set the tone for their handling of the crisis. At their meeting Hirota informed Grew of the sinking and expressed “the profound apologies and regrets” of the Japanese Government. He also represented that the Japanese government would fully compensate for any loss. Grew admitted that, “he (Hirota) seemed genuinely moved”. The Embassy received a message from the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly before Hirota’s arrival with the instructions that Grew read its contents to the Japanese diplomat. In his note, President Roosevelt demanded “an apology, indemnities, punishment of the officers involved, and assurances that similar incidents would not happen again.” The following day Yoshizawa delivered a note from Hirota addressed to Grew expressing apologies for the “disaster” thus establishing the Japanese desire to satisfy American demands.

Japanese military men also engaged in such good will gestures. Captain Nabutake Kondo of the Imperial Navy, Senior Aide to the Navy Minister, called on the American Naval Attache, Captain Harold Bemis, at the chancery on 15 December to express the regrets of the Imperial Navy for the incident. Kondo outlined a number of operational rules instituted by the Imperial Navy to safeguard against a repeat of the Panay sinking. One of the new rules required that any element of the Japanese military operating in the presence of neutral shipping sacrifice engaging enemy targets “to avoid the recurrence of a similar mistake.” Indeed a reassuring gesture. Kondo also informed Bemis that the commanding naval air corps officer in Shanghai, as the officer responsible for the unit which made the attack, had been relieved and recalled to the home islands.21 Actually the Imperial Navy allowed Rear Admiral Teizo Mitsunami, Commander Second Combined Air Group, Shanghai, to resign his post. It may seem that there is little difference between tendering one’s resignation and being dismissed from duty, but being informed of the dismissal of the officer in charge of the squadron that sank the Panay certainly gave the appearance of the Imperial Navy taking drastic measures against those responsible. It is unfortunate that the career of Admiral Mitsunami ended as a result of the Panay sinking because his minimal culpability in the incident. He returned to Japan and never received another combat command during the rest of his career with the Imperial Navy.

The Imperial Navy acted shrewdly in the fallout of the Panay sinking. As in all hierarchies, accountability fell on someone in a position of authority (Mitsunami) and the sacrifice of his career gave the appearance that the institution, in this case the Imperial Navy, had no control over the malfeasance or misfeasance of one individual officer. This action portrayed Mitsunami as a careless, irresponsible leader and suggested that he by no means represented the entire officer corps of the Imperial Navy. To cultivate the image of Mitsunami as an aberration, several high ranking naval officers participated in a conference at the American Embassy in Tokyo on 22 December. Organized by Ambassador Grew and designed to ascertain an undistorted understanding of the facts surrounding the accident, the Imperial Navy’s participation in this conference constituted no more than a “good will” gesture. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto attended.

At this conference the Japanese officers presented an argument for the defense of the Navy. The argument revolved around the Army intelligence reports that, supposedly inspired the attack. The Navy operated its aircraft from land bases during most of the war with China primarily because the Chinese Navy could not compare to the strength of the Imperial Navy. Since infantry units decided the war in China, contribution of air squadrons constituted the bulk of the Imperial Navy’s role therein. Naval airgroups maintained their unit integrity while depending on the Imperial Army for intelligence reports. On the morning of the 12 December, an Army unit reported the spotting of several boats fleeing the fighting around Nanking packed full of Chinese soldiers. Due to a lack of available aircraft, the Army requested that the naval air arm make the attack. The 13th Air Group of Mitsunami’s 2nd combined Air Group relied on that report. Lieutenant Masatake Okimaya23 led six of the twelve Yokosuka B4Y Type 96 dive bombers in the attack on the Panay.

In 1953 he commented on the raid:

Since the outbreak of hostilities there had been a standing order to avoid bombing of vessels on the Yangtze because of the danger of involvement with foreign neutrals. But learning of these obviously legitimate targets, we were thrilled when Captain Miki gave the order for all available aircraft to participate in the attack.

The Navy had an out. Shifting first to Mitsunami, blame then fell on the individual pilots who led sections in the attack. Thereby, the Navy disassociated itself from any blame. The Navy did this to give the appearance that it did not support such activity. The Army could not be blamed either because it only provided the intelligence reports to the Navy. Hierarchies are set up in such a way as to isolate and blame one culprit in disastrous situations. On 19 December, Okimiya had the distinction of being the first Japanese pilot to land at Tachiochang Field in the Japanese controlled city of Nanking. However, all pride in this accomplishment disappeared when, on the next day, he received a letter of reprimand for hi s participation in the raid of 12 December. A special airmail courier delivered the document. The citation charged him with “failing in the performance of his duties” because he did not “definitely” identify the target of an attack (the Panay). If indeed the Japanese contention that, the Panay sank as a result of a case of mistaken identity is the truth, then Okimiya’s reprimand seems well placed, but by that same token Mitsunami’s dismissal seems un-called for. Three other officers received the same reprimand as Okimiya. The Japanese strayed from standard operating procedure in administering these reprimands in that Admiral Yonai himself wrote and signed them rather than the pilot’s immediate commanding officer. Admiral Yonai’s direct issuing of the censures is indicative of the Navy’s desire to deal with the matter quickly and shed its responsibility to administer discipline. Once again the Imperial Navy demonstrated its desire to prove to the United States that the incident called for extreme actions.

While the Japanese government and military offered apologies, the people of Japan exhibited remorse as well. It is customary in Japan that condolences and expressions of grief take the form of cash donations. The American Embassy, Japanese newspapers and various Japanese governmental offices received such cash donations as early as 16 December. In fact, personnel of the Japanese 3rd Fleet offered a large sum to the Commander-in-Chief, United States Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Harry Yarnell. Ambassador Grew astutely recognized a delicate situation in the making. Grew worried that acceptance of the donations might “prejudice the principal of indemnification.”

Uncomfortably though, refusal to accept such a gift is a grievous insult to Japanese tradition. Faced with this concern, Grew requested the advice of Secretary of State Cordell Hull. The Secretary realized that rejection of the sincere gifts of the Japanese people would aggravate an already tense matter. Adherence to proper etiquette demanded that those interested in offering that type of expression of their feelings should be allowed to do so. Hull therefore suggested the establishment of a fund with a prominent Japanese citizen as the recipient. Advertisements would inform the Japanese people where to send donations, and the funds would be devoted to something in Japan which would contribute to the good will of the two countries. The handling of this issue displayed the will of the- diplomats involved to not only ‘resolve the incident, but to continue the development of friendly relations.

Lieutenant Commander J.J. Hughes

Grew observed other expressions of regret; One well-dressed Japanese woman stepped behind a door in the chancery and cut off a big strand of her hair and gave it to us with a carnation – the old-fashioned gesture of mourning the loss of a husband. Another Japanese broke down and cried at his country’s shame.

This public outcry involved members of every facet of Japanese society. High government officials, doctors, lawyers, businessmen, professors, doctors, and even school children visited the American Embassy in Tokyo to convey their shame. School children across Japan wrote letters and poems of the same sentiment to Ambassador Grew (see introduction). Sparing no effort to extend every possible diplomatic courtesy to one another helped to calm the tension between the United States and Japan in the wake of the Panay incident.

On 23 December, Secretary of State Hull received the findings of the Naval Court of Inquiry which the United States Navy convened to investigate the Panay sinking. The report absolved all American servicemen and civilians of any negligence or misconduct with regards to the events of 12 December 1937. Article 5 of the Naval court of inquiry findings placed responsibility for all losses on the Japanese. That evening a number of representatives of the Japanese government, the Imperial Army, and the Imperial Navy visited Grew at the American Embassy to share the findings of their own inquiry. In line with the initial Japanese reaction, their inquiry admitted Japanese liability and again offered apologies, but hinted at the accidental nature of the attack.

Christmas Eve 1937 brought the Japanese government’s official statement on the issue of the Panayattack. In a note delivered to the American Embassy, Hirota met all four of President Roosevelt’s demands. Only one issue remained unresolved: the money. The United States presented Japan with a statement of loss for the promised indemnifications on 19 March 1938. It included property loss restitution and indemnification for death and personal injury claims. The United States government billed the Japanese government in the amount of $2,214,007.36 and the Japanese delivered a check for that exact amount on 22 April 1938. On that day, the Panay sinking as a diplomatic crisis ended.

Ambassador Grew’s impressions of the meaning of the Panay incident ranged from naive exuberance to insightful foreboding. He believed that the Japanese purposely delayed their official response until 24 December in an effort to capitalize on the “Peace on Earth, good will toward men” spirit associated with the Christmas holidays. That is not to say that Grew regarded the Christmas Eve statement with contempt. On the contrary, Grew felt it to be a “masterful” approach to diplomacy. Although aware of the intent behind the timing of the Japanese statement, his excitement led him to refer to it as “an eminently happy day.” Grew’s diary entry for 26 December 1937 praised the diplomatic skill used by both countries to avoid war. He believed that the immediate tendering of apologies by the Japanese soothed the United States into a desire to be lenient’ and encouraged the rapid acceptance of those apologies. However, he confessed the temporary nature of the diplomatic accomplishments involving the Panay incident when he said, “We have, for the moment, safely passed a difficult hurdle.” The Panay incident emphasized to the United States the existence of “two Japans”.

Grew assessed the growing rift between the Japanese military and the Japanese government as the source of future concern, and correctly diagnosed the need for the government to exert control over its military. Secretary of State Hull believed that “wild, runaway, half-insane Army and Navy officials” precipitated the attack. Hull’s comment is quite accurate when viewed with reference to the ideological doctrine that guided the Japanese military in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Panay sinking occurred during the twilight of Japanese pre-WorId War II diplomacy. While diplomatic representatives dealt with the foreign office their power remained in checked because the Imperial Army actually developed Japan’s foreign policy from 1931 onward. Some of the higher echelons of the Japanese military became disciples of Kodo-Ha; a movement reminiscent of the days before the influence of Western culture. Prior to the 20th Century, the “samurai”, or warrior class, represented the highest tier in Japanese society. This structure still existed when Japan opened its doors to westerners in the late 1800s, and as a result many Japanese men continued to feel strong ties to the Samurai past well into the 20th Century. To the ancestors of this formerly exalted warrior class, Kodo-Ha offered pride and status for men struggling to find a place in a burgeoning capitalist society. Japan did not part with its Samurai past to form any semblance of a governing assembly until the establishment of the Diet in 1920. In response to the Diet’s ascendancy to power, the Army staged two international incidents during the 1930s to challenge its authority. In September 1931 Chinese saboteurs allegedly exploded a bomb along the South Manchuria Railroad. The Imperial Army Commander in the region, a Kodo-Ha disciple, threw his forces into battle without the Diet’s approval. Then came the “strengthening” of Japanese forces in China in response to the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge in July 1937. The existence of a state of war with China gave the military constitutional control over the government. The Japanese military then moved to accomplish the fundamental goal of Kodo-Ha; Hakko Ichiu or the “liberation” of Asia. This called for the creation of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere; an Asia under the domination of Japan.

The Panay sinking occurred during the twilight of Japanese pre-WorId War II diplomacy. While diplomatic representatives dealt with the foreign office their power remained in checked because the Imperial Army actually developed Japan’s foreign policy from 1931 onward. Some of the higher echelons of the Japanese military became disciples of Kodo-Ha; a movement reminiscent of the days before the influence of Western culture. Prior to the 20th Century, the “samurai”, or warrior class, represented the highest tier in Japanese society. This structure still existed when Japan opened its doors to westerners in the late 1800s, and as a result many Japanese men continued to feel strong ties to the Samurai past well into the 20th Century. To the ancestors of this formerly exalted warrior class, Kodo-Ha offered pride and status for men struggling to find a place in a burgeoning capitalist society. Japan did not part with its Samurai past to form any semblance of a governing assembly until the establishment of the Diet in 1920. In response to the Diet’s ascendancy to power, the Army staged two international incidents during the 1930s to challenge its authority. In September 1931 Chinese saboteurs allegedly exploded a bomb along the South Manchuria Railroad. The Imperial Army Commander in the region, a Kodo-Ha disciple, threw his forces into battle without the Diet’s approval. Then came the “strengthening” of Japanese forces in China in response to the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge in July 1937. The existence of a state of war with China gave the military constitutional control over the government. The Japanese military then moved to accomplish the fundamental goal of Kodo-Ha; Hakko Ichiu or the “liberation” of Asia. This called for the creation of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere; an Asia under the domination of Japan.

Grew correctly realized that diplomacy is only effective when the diplomats wield power. During the 1930s, Japanese politicians exerted less governmental authority than the military. The absence of a system of “checks and balances” in the Japanese constitution of 1889 set the stage for a military coup d’état, and recognizing this, the militarists exploited that loophole and accessed absolute political power. The provision allowing the military to assume full governmental authority in the event of war provided the Kodo-Ha disciples their window of opportunity to eclipse the Western notion of diplomacy, and disarm their own statesmen. In late 1937 and early 1938, Japanese diplomats functioned as nothing more than the pawns of the warrior class. The phase of Hakko lchiu most likely to elicit American objections and lead to war required secure control of East Asia as a whole. The Japanese military needed to consolidate and make several more minor gains in 1937 before the implementation of that component of the plan. The ability to launch the massive offensives of 1941 and 1942 required several years of strengthening. Therefore, the Kodo-Ha disciples in the Army and Navy welcomed the improvement of Japanese-American relations brought on by the skillful work of the diplomats because it bought time. As the Panay incident proved, Japanese statesmen before 1941 sincerely struggled to repair the relations that the military jeopardized with the campaigns in the East called for by “Hakko Ichiu.”

Surprisingly few Americans recognized the emerging military regime’s domination of Japanese politics. Joseph Grew, who ref erred to the “two Japans,” questioned the Japanese government’s ability to exert control over its military and therefore distinguished himself as one of the few people to sound a warning as to problems that 1941 would bring. The life of the relationship salvaged by the resolution of the Panay sinking depended on the military’s influence in Japanese foreign affairs diminishing. That could not happen because Hakko Ichiu influenced too many soldiers and sailors to be easily discarded. American abandonment of the adversarial view of Japan’s Asian expansion also could have maintained good relations. That could not happen either because of America feared Japanese political hegemony in the East. The foreign policies of the United States and Japan put the two countries on a collision course reversible by nothing short of war.

Surprisingly few Americans recognized the emerging military regime’s domination of Japanese politics. Joseph Grew, who ref erred to the “two Japans,” questioned the Japanese government’s ability to exert control over its military and therefore distinguished himself as one of the few people to sound a warning as to problems that 1941 would bring. The life of the relationship salvaged by the resolution of the Panay sinking depended on the military’s influence in Japanese foreign affairs diminishing. That could not happen because Hakko Ichiu influenced too many soldiers and sailors to be easily discarded. American abandonment of the adversarial view of Japan’s Asian expansion also could have maintained good relations. That could not happen either because of America feared Japanese political hegemony in the East. The foreign policies of the United States and Japan put the two countries on a collision course reversible by nothing short of war.

I left the Minister’s house realizing only too clearly that our satisfaction at the settlement of thePanay incident may be but temporary and that the rock upon which for five years I have been trying to build a substantial edifice of Japanese-American relations has broken down into treacherous sand.

The accidental sinking of one relatively small gunboat in the midst of a foreign war hardly seems like a profound and utterly distressing event with international ramifications. It did result in a small scale loss of life and property which temporarily angered the people of the Unites States. Although two Americans and one Italian died, the people of the United States demonstrated their ability to quickly forget the dead, the survivors, and the diplomats who resolved the matter. Although Japanese diplomats corrected the situation as best they could, the United States still ranked among the countries affected by Japanese expansionist aggression in the days before World War II. This caused at least one American diplomat (Grew) to speculate as to the future. Most Japanese did not recognize the ability to employ “wisdom and good sense” in an effort to resolve conflict as amiable. Thus one of the most commendable instances of diplomatic conflict resolution in the 20th Century passed unappreciated by the country that initiated the effort. The basis of the problem revolved around Japan’s feudal tendency to ennoble the warrior over the statesmen. Moreover, while Japan possessed all of the technological advancements of the world, these wonders lacked a modern political structure to monitor their use and consequently another world war resulted.